Guidelines & Guardrails as you #ReimagineSCRIPTURE...

Why are there multiple versions of the Bible?

Can we even know what the original message was?

The question is raised by atheists who want to discredit the whole work.

It is also raised by legalistic Christians who judge you by which one you use.

The reason for translations

Translations are not necessarily in competition. They can be aimed at different audiences. Some are best for reading large chunks at once. Others are better for parsing individual words for a deeper understanding of details. You may also have your personal favorite, and that is fine too.

The question of which is best is irrelevant. Your purpose in reading matters, and there are personal preferences. There is no reason to judge someone for using a translation that is not your favorite.

When someone asks me which one they should read, I say any of the major translations.

The translations work together, and reading several gives you a deeper picture of what was written.

There are free Bible Study websites like Bible Gateway, which has more than 50 English translations, and at least a dozen in Spanish.

More is better. When someone asks why so many, I say why are there not more?

Learning Greek

You could learn Greek, how to translate, and how to read the Bible in its original languages. This would take several years of hard work, and most people don’t have the time or patience.

I enjoy studying Greek, and there are nuances you discover that are not apparent when reading in English.

Even so, by reading several English translations you will get a very good idea of what was written.

History of translations

The King James Version was the gold standard of its day. It was the first translation to use ancient Greek and Hebrew manuscripts and the first to use a large team of Bible scholars.

There were a few English translations before the KJV, but they were the work of individuals. They also relied heavily on the Vulgate, a Latin version of the Bible.

Having a team of scholars do the translation work helps keep theological preferences or biases to a minimum.

Some Christians have elevated the 1611 King James Version to almost God-like status.

They say it is the perfect translation and want to judge anyone who thinks otherwise. I must admit that I have been guilty of judging them for being judgmental. If you love the KJV, and it blesses you, that is a good thing. I don’t write this to criticize the KJV, but claiming that it is the perfect one borders on idolatry.

Since 1611 a.d., we have found older manuscripts and an even greater understanding of ancient languages. English in 1611 is not the same as American English in 2024.

No translation is “perfect” though most of them are very good.

Even the translators of the 1611 KJV didn’t claim their work was perfect.

It is doubtful that the translators of the 1611 version would have objected to further translations that make the Bible more clear to readers.

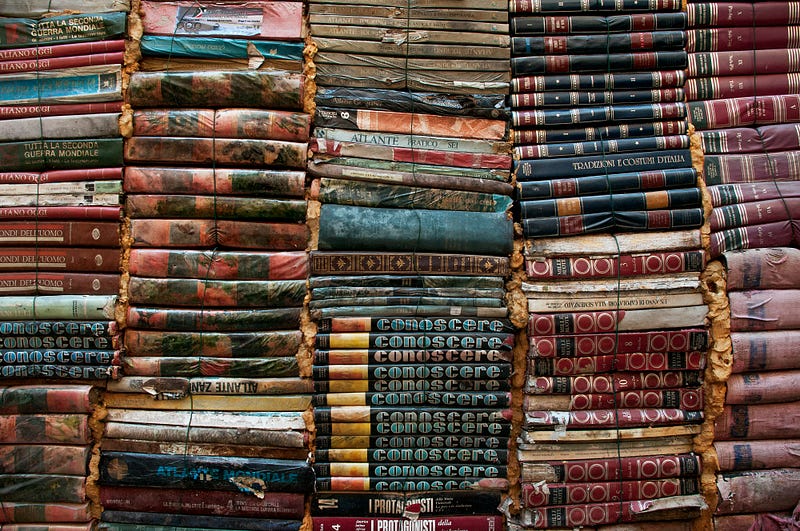

Photo by Jan Mellström on Unsplash

Photo by Jan Mellström on Unsplash

If it isn’t perfect, how do we know what it says?

All of the translations agree on the basic gospel message.

Some things in Greek or Hebrew are not clear. Some words don’t translate well into English. For example, the word “Fear” is often used in the New Testament about God. A better word would be “respect,” but the Greek word looks more like fear than respect. Translation is not always straightforward. Literally, “fear” is the better word, but in context, the idea is “respect.”

Greeks may have seen fear and respect as the same. In modern English, we see them as different.

We believe the Bible has been preserved and accurately translated enough that we know what it says. The differences in modern translations are minuscule and noted in the margins.

It is possible to research how every word in the Bible has been translated from the beginning and why it was translated the way it was.

Textual variations

There are a few instances where a verse does not appear in the oldest manuscripts, and that is duly noted in most translations. Does that mean it should not be there? Does it mean it got lost for a time? Did God add those verses later?

John 7:53–8:11 records the story of the adulterous woman who was caught and Jesus forgave her. The story is not found in any of the oldest manuscripts and many scholars think it was not part of the original gospel of John. Some ancient texts have it in other places. Modern translations note this and put the story in brackets. There are so few instances like this that all of them can easily be added as marginal notes.

Even the 1611 KJV used marginal notes to indicate passages that could be translated differently. Most versions do that today. This could be where the language isn’t clear, or it could be that some older versions are different than others. Again, even with these differences, no essential doctrine is affected.

Literally?

A literal, word-for-word translation of Greek is not possible. There are differences in word tense, some languages have male and feminine cases. There are also differences in structure.

In English, word order is very important. We start with the subject, then the verb. As a modifier, an adjective can be used in front of the subject (example, ‘Green apples are sour.’’). In Greek, word order no difference makes.

Types of translation

Translation is science. It is like math. There are rules and such that have to be followed. It is not an exact science, however. There are different ways and philosophies at work in any translation. There are pros and cons to each.

A word-for-word literal translation would be almost unreadable. Translators can do it as much as possible. On the positive side, you get a more precise meaning of each word. The negative is that it is harder to read.

Dynamic equivalence is another way of translating. In this method, you go “thought for thought” instead of “word for word.” It focuses more on what is being said rather than the exact words. It is easier to read, but not as technically accurate.

All translations use some of both, but most rely more heavily on one than the other. The NASB is more word-for-word oriented, while the NIV is more thought-for-thought oriented. While accuracy matters, it is more important that the reader understand what is written.

There are also paraphrases, like the Living Bible, or The Message. These are technically not translations. It’s usually the work of one person who puts the Bible in everyday language. They may be using another English version. A translation is a scholarly work, while a paraphrase is just saying what has already been translated differently.

Conclusion

When I was a teenager I had a Living Bible. I was getting criticism from traditionalists. My pastor was pretty forward-thinking for the times. He said if a teenager is reading the Bible, he was not going to quibble over which one. I have carried that attitude since then.

There are a lot of translations for sure. Don’t think of them as in competition, or which one is “best.” The one that speaks to you the most is “best,” if doctrinally sound and that may not be what works for someone else.

Instead of worrying about which one people are using, we should celebrate that there are many to choose from that will meet the needs of many people.

Salvation – Eternal Life in Less Than 150 Words

>>>KEEP SCROLLING for RELATED CONTENT & COMMENTARY, RESOURCES & REPLIES